"How broken is the US Health Care System? Let Us Count the Ways" - NPR.org

"... perhaps as many as 98,000 people, die in hospitals each year as a result of medical errors that could have been prevented, according to estimates from two major studies." - Institute of Medicine media files

It seems we can't find enough problems with US health care: the uninsured, excessive costs, real preventable medical errors continue to occur, patient safety lapses, handwashing snafus - you name it. But have no fear: from cameras in the OR, patient check-in kiosks, smart phone apps, to fancy schmancy electronic medical records, technology will save us.

At least that's the rage these days.

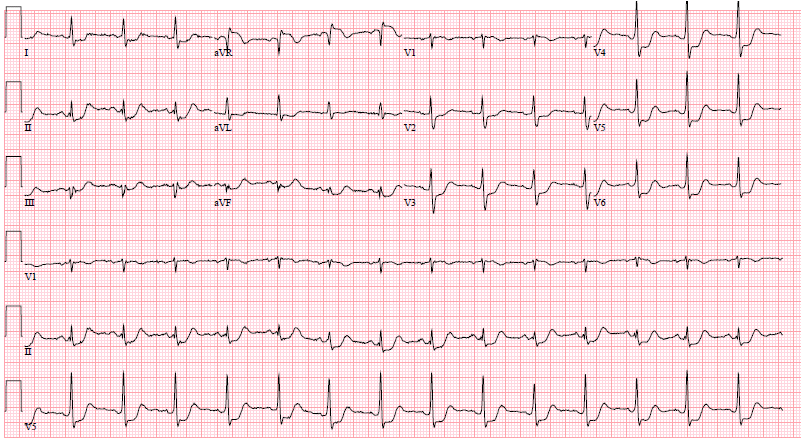

But are we dumbing down our doctors and medical personnel with technology as a result? Yesterday I was called to evaluate a patient for a possible emergent pacemaker implant. Reviewing his chart, he had been given beta blockers intravenously in the early morning hours along with a hefty dose of enoxaparen (because of the presence of atrial fibrillation and an EMR-generated alert to consider DVT prophylaxis). Unfortunately, because enoxapren has no antidote for bleeding and there was another cause for bradycardia, the pacemaker wasn't needed. But this episode got me thinking.

Increasingly we're using technology for social engineering of our doctors and nurses in medicine. I believe this is the part of technology's use that disturbs physicians so. Doctors understand the "good" uses of technology: one that provides instant information that facilitates decision making and doesn't restrict behaviors. But increasingly with the development of rigid "guidelines" and "acceptable use criteria" paired with electronic care pathways, doctors who were once considered guild-masters of their trade, are increasingly seen as nothing more than journeymen and task-masters for data entry as they feed decision support systems for payment from third parties.

An important article for doctors appeared in the Wall Street Journal on Saturday, but I suspect most doctors missed it. The article, written by Evgeny Morozov, was entitled "Is Smart Making Us Dumb?" We should all read it with an eye toward what's happening in medicine. In the article, Morozov sounds a cautionary note about this coming technology revolution in medicine: that "social engineering is being disguised as product engineering."

"But there is reason to worry about this approaching revolution. As smart technologies become more intrusive, they risk undermining our autonomy by supressing behaviors that someone somewhere deems undesireable."Morozov differentiates technologies that are "good smart" from "bad smart." "Good smart" technologies leave us completely in control of the situation and seek to enhance our decision making by providing more information. Technology that is "bad smart" make certain choices and behaviors impossible. Even the "suggestions" these devices give to doctors can be detrimental to care since they inherently fail to consider future events that might need to occur for a patient (as in my pacemaker case described earlier).

In our rush to develop a Utopian vision for error-free health care using technology, we should consider the implications of such a world for medicine. Morozov uses a valuable anology: Autopia.

"Will those autonomous spaces be preserved in a world replete with smart technologies? Or will that world, to borrow a metaphor from the legal philosopher Ian Kerr, resemble Autopia—a popular Disneyland attraction in which kids drive specially designed little cars that run through an enclosed track? Well, "drive" may not be the right word. Though the kids sit in the driver's seat and even steer the car sideways, a hidden rail underneath always guides them back to the middle. The Disney carts are impossible to crash. Their so-called "drivers" are not permitted to make any mistakes."And we should ask what consequences of medical students, residents, and newly minted medical attendings being unable to "crash" might be:

"Creative experimentation propels our culture forward. That our stories of innovation tend to glorify the breakthroughs and edit out all the experimental mistakes doesn't mean that mistakes play a trivial role. (Editors note: someone else said something like this before) As any artist or scientist knows, without some protected, even sacred space for mistakes, innovation would cease.Precisely.

With "smart" technology in the ascendant, it will be hard to resist the allure of a frictionless, problem-free future. When Eric Schmidt, Google's executive chairman, says that "people will spend less time trying to get technology to work…because it will just be seamless," he is not wrong: This is the future we're headed toward. But not all of us will want to go there.

A more humane smart-design paradigm would happily acknowledge that the task of technology is not to liberate us from problem-solving. Rather, we need to enroll smart technology in helping us with problem-solving. What we want is not a life where friction and frustrations have been carefully designed out, but a life where we can overcome the frictions and frustrations that stand in our way. Truly smart technologies will remind us that we are not mere automatons who assist big data in asking and answering questions."

-Wes